19 July 1989 - United 232

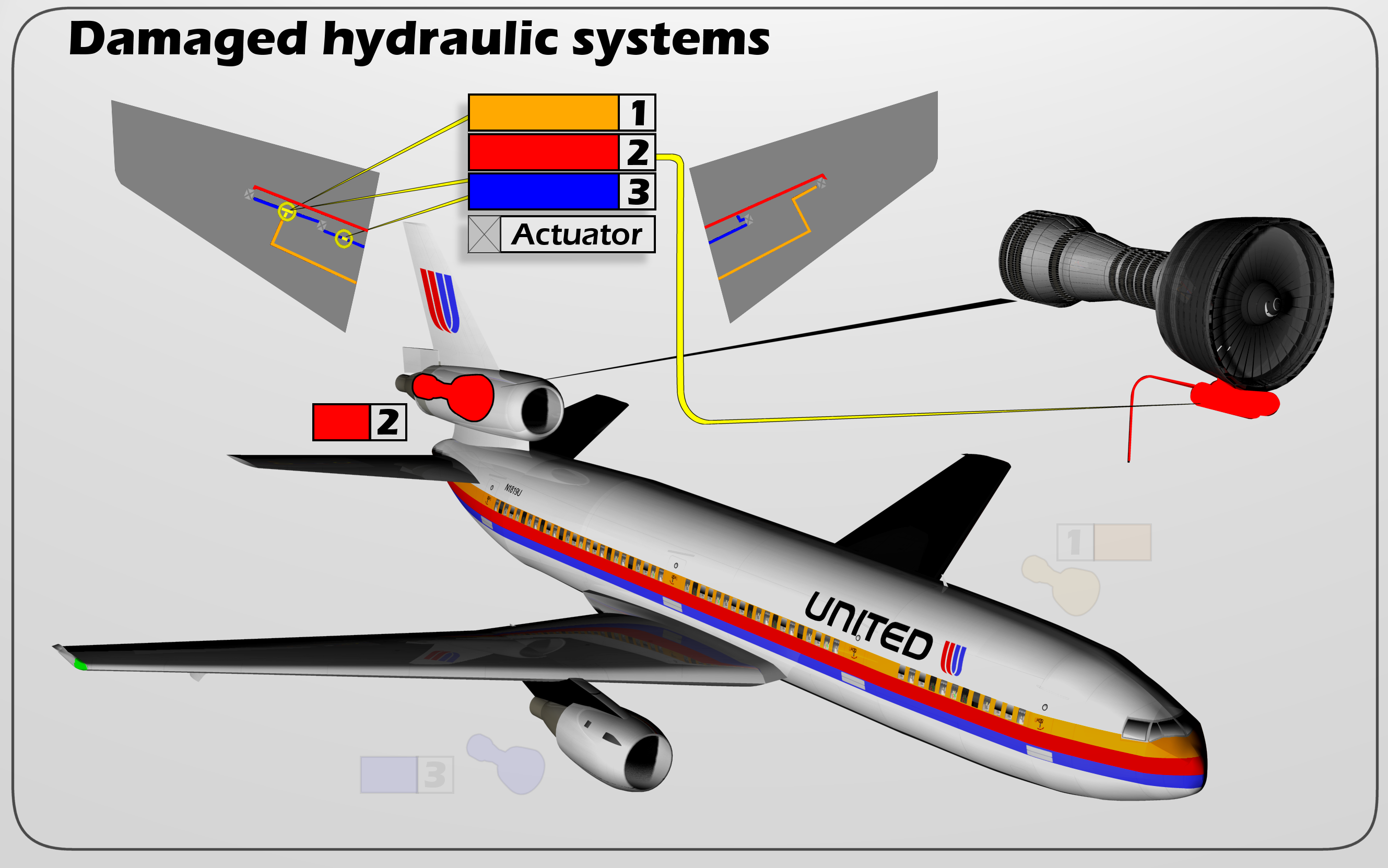

United Airlines flight 232 was a scheduled flight from Stapleton International Airport, in Denver, Colorado, to O'Hare International Airport in Chicago, Illinois, and then would continue on to Philadelphia International Airport in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. On July 19, 1989, the Douglas DC-10 (Registration N1819U) suffered an uncontained failure of its number 2 engine. Shrapnel was hurled from that engine with enough force to penetrate the hydraulic lines of all three of the aircraft's hydraulic systems. The hydraulic fluid from each system was rapidly dissipated, and that resulted in no flight controls working except the thrust levers for the two remaining engines. The aircraft broke up during an emergency landing on the runway at Sioux City, Iowa, killing 110 of its 285 passengers and one of the 11 crew members.

Owing to the skill of the crew and a DC-10 instructor pilot, who was a passenger on the aircraft, 174 passengers and 10 crew members survived the crash. The disaster is considered an example of successful Crew Resource Management, due to the effective use of all the resources available aboard the plane for help during the emergency.

The flight took off at 14:09 (CDT) from Stapleton International Airport, Denver, Colorado, bound for O'Hare International Airport in Chicago, Illinois with ongoing service to Philadelphia International Airport in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. At 15:16, while the plane was in a shallow right turn at 37,000 feet, the fan disk of its tail-mounted General Electric CF6-6 engine failed and disintegrated, the debris from which was not contained by the engine's nacelle. Pieces of the structure penetrated the aircraft tail section in numerous places, including the horizontal stabilizer. The pieces of shrapnel punctured the lines of all three hydraulic systems, allowing the fluid to drain away.

Captain Alfred C. Haynes and his flight crew (First Officer William Records, who was flying, and Second Officer Dudley Dvorak, flight engineer) felt a jolt going through the aircraft, and warning lights showed that the autopilot had disengaged, and the tail-mounted number two engine was malfunctioning. The co-pilot noticed that the airliner was off course, and moved his control column to correct this, but the plane did not respond. The flight crew discovered that the pressure gauges for each of the three hydraulic systems were registering zero, and they realized that the initial failure had left all control surfaces immovable. The three hydraulic systems were separated such that a single event in one system would not disable the other systems, but lines for all three systems shared the same ten-inch wide route through the tail where the engine debris penetrated, and beyond that there was no backup system, a fact which the NTSB later recommended be remedied.

The plane had a continual tendency to turn right, and was difficult to maintain on a stable course. It began to slowly oscillate vertically in a phugoid cycle, which is characteristic of planes in which control surfaces command is lost. With each iteration of the cycle the aircraft lost approximately 1500 feet of altitude. Dennis E. Fitch, a DC-10 flight instructor, was deadheading as a passenger on the plane and offered his assistance. After entering the cockpit, Fitch discovered that the flight crew had resorted to a method of controlling the aircraft through adjusting the throttles of the remaining two engines; running one engine at higher power than the other to turn the plane (differential thrust), and accelerating or decelerating in order to gain or lose altitude. Using this method, it was possible to mitigate the phugoid cycle and make rough steering adjustments. At one point Fitch manually lowered the landing gear in flight, hoping that this would force trapped hydraulic fluid back into the lines allowing some movement of control surfaces. Although the gear lowered successfully, there was no improvement in control response as all the fluid had been lost through the punctured lines.

Air traffic control (ATC) was contacted and an emergency landing at nearby Sioux Gateway Airport was organized.

Haynes kept his sense of humor during the emergency, as recorded on the plane's CVR:

Fitch: I'll tell you what, we'll have a beer when this is all done.

Haynes: Well I don't drink, but I'll sure as hell have one.

and later: Sioux City Approach: United Two Thirty-Two Heavy, the wind's currently three six zero at one one; three sixty at eleven. You're cleared to land on any runway.

Haynes: [laughter] Roger. [laughter] You want to be particular and make it a runway, huh?

A more serious remark often quoted from Haynes was made when ATC asked the crew to make a left turn to keep them clear of the city:

Haynes: Whatever you do, keep us away from the city.

Haynes later noted that "We were too busy [to be scared]. You must maintain your composure in the airplane or you will die. You learn that from your first day flying."

Landing was originally planned on the 9,000 foot (2743 m) Runway 31. The difficulties in controlling the aircraft made lining up almost impossible. While dumping excess fuel, the plane executed a series of mostly right-hand turns (it was easier to turn the plane in this direction) with the intention of coming out at the end lined up with runway 31. When they came out they were instead left with an approach on the shorter Runway 22 of 6,600 feet (2012 m), with little capacity to maneuver.

Fire trucks had been placed on runway 22, anticipating a landing on runway 31, and there was a scramble as the trucks rushed out of the way. All the vehicles parked there got out of the way before the plane touched down.

Fitch continued to control the aircraft's descent by adjusting engine thrust. With the loss of all hydraulics, the crew were unable to control airspeed independent from sink rate. On final descent, the aircraft was going 240 knots and sinking at 1850 feet per minute, while a safe landing would require 140 knots and 300 feet per minute. The aircraft began to sink faster while on final approach and veer to the right. The tip of the right wing hit the runway first, spilling fuel which ignited immediately. The tail section broke off from the force of the impact and the rest of the aircraft bounced several times, shedding the landing gear and engine nacelles and breaking the fuselage into several main pieces. On the final impact the right wing was sheared off and the main part of the aircraft skidded sideways, rolled over on to its back, and slid to a stop upside down in a corn field to the right side of runway 22. Witnesses reported that the aircraft cartwheeled but the investigation did not confirm this. News reports that the aircraft cartwheeled were due to misinterpretation of the video of the crash that showed the flaming right wing tumbling end-over-end. Debris from Engine #2 (including the fractured fan disk) and other parts from the tail structures of the plane, were later found on farmland near Alta, Iowa, approximately 60 miles northeast of Sioux City.

The plane landed askew, causing the explosion and fire seen in this still from local news station video.Of the 296 people on board, 111 died in the crash. Most were killed by injuries sustained in the multiple impacts, but many in the middle fuselage section directly above the fuel tanks died from smoke inhalation in the post-crash fire, which burned for longer than it might have due to delays in the firefighting efforts. The majority of the 185 survivors were seated behind first class and ahead of the wings (one of the crash survivors died a month later of his injuries). Many passengers were able to walk out through the ruptures to the structure, and in many cases got lost in the high field of corn adjacent to the runway until rescue workers arrived on the scene and escorted them to safety.

Download the full NTSB report

LINK to the CVR transcript, courtesy of the AviationSafetyNetwork.